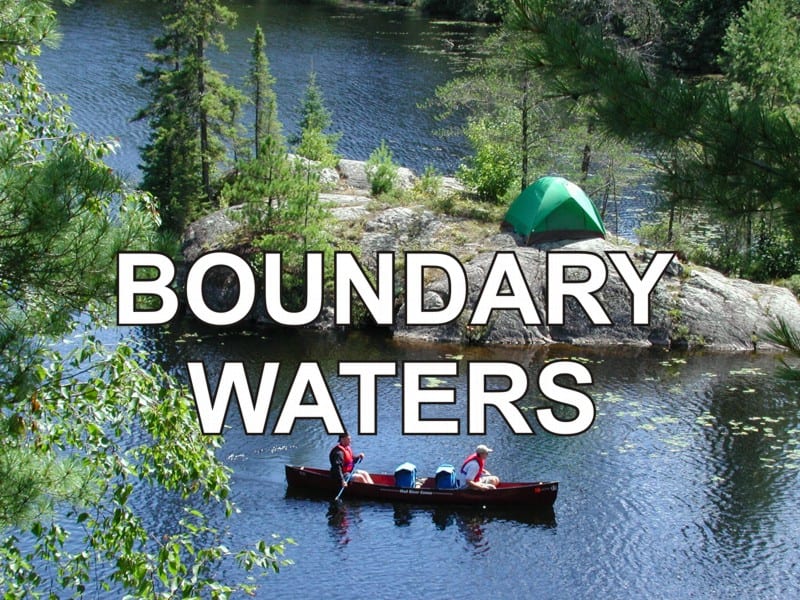

My brother, Mike moved to Minnesota in 1966 after graduating from college. A couple of years later, in August 1969, he suggested we go on an adventure together. He had discovered an interesting area in upper Minnesota, known as The Boundary Waters Canoe Area(BWCA). This region straddling the USA-Canadian border between Minnesota and Ontario just west of Lake Superior, is a part of the Superior National Forest in Minnesota and La Verendrye and Quetico Provincial Parks in Ontario. This wilderness area got its name from the “Boundary Waters Treaty” of 1909 between the USA and Canada ratified by President William Taft and King Edward VII of the United Kingdom.

So, we started making plans for this adventure in the wilderness, which would take place in August of 1969, when Mike was 25 and I was 17. Mike had contacted Saganaga Canoe Outfitters and we began accumulating the items we thought we would need for the trip. I rented a tent in Waukegan, borrowed a two-burner, camp stove from Uncle Orson Howard, purchased a backpack, a mess kit and a combination shovel/pick. In addition to all this, I brought a sleeping bag, air mattress, white-gas, powered Colman lantern and clothes. Although it seems a bit odd to me now (I hope it made sense at the time), but I brought all this stuff to the airport and took a plane to the Minneapolis/St. Paul Airport, and began my 700-mile journey from Zion, Illinois to the uncharted waters of the unknown.

Mike picked up me and all the accumulated equipment at the airport and the next day we went out and bought food and other supplies, which included two, three-foot machetes from the Army Surplus Store. We managed to cram everything (except the Coleman Lantern) into his Chevrolet Corvair. The Corvair became infamous as the main subject of consumer advocate, Ralph Nader’s book, “Unsafe At Any Speed.” We then headed north from St. Paul via route 35 to Duluth, where we picked up route 61 and traveled along the coast of Lake Superior. We decided to stop at a campground for the night, which would give us practice setting up the tent.

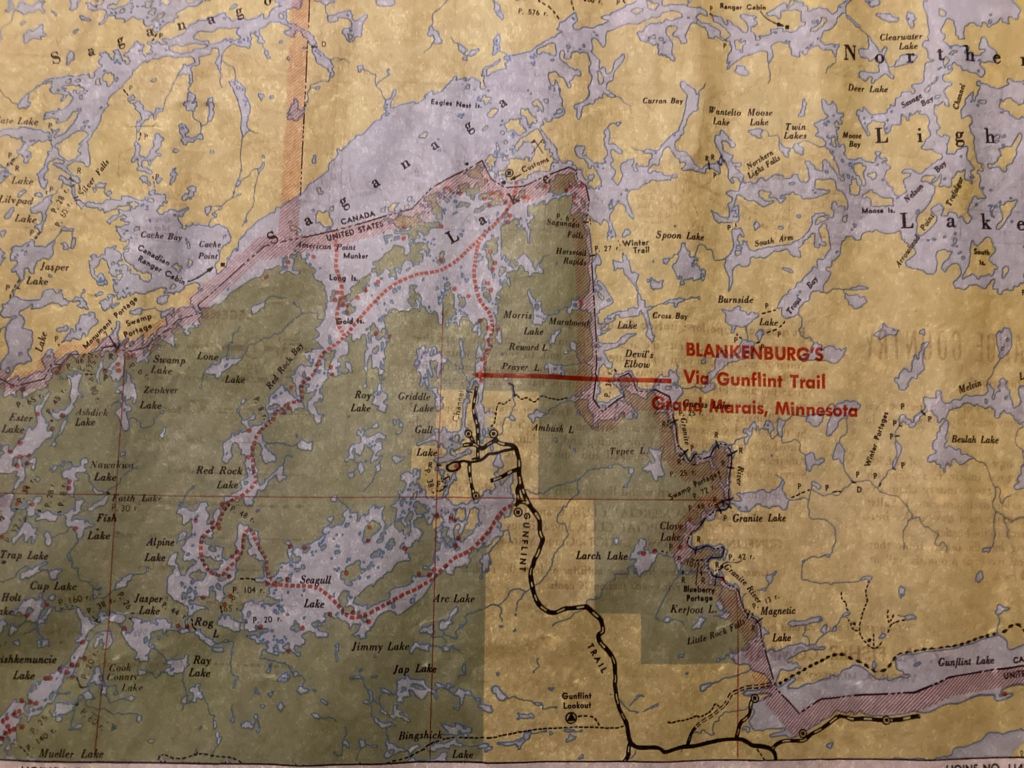

The next day, we reached Grand Marais and the beginning of the historic Gunflint Trail. The Ojibwe Indians, known for their excellent birch bark canoes, inhabited the boundary water areas in the USA and Canada. The Ojibwe tribe was popularized in Henry W. Longfellow’s poem, “The Song of Hiawatha.” One of their trails evolved into the Gunflint Trail, which was named after a large deposit of flint rock on the shores of a lake, known as the Gunflint Lake. The Indians used flint for arrowheads, cutting tools and to create sparks to start fires. Firearms with a flint firing system, called a flintlock, were used for over two centuries, thus we have the name, Gunflint.

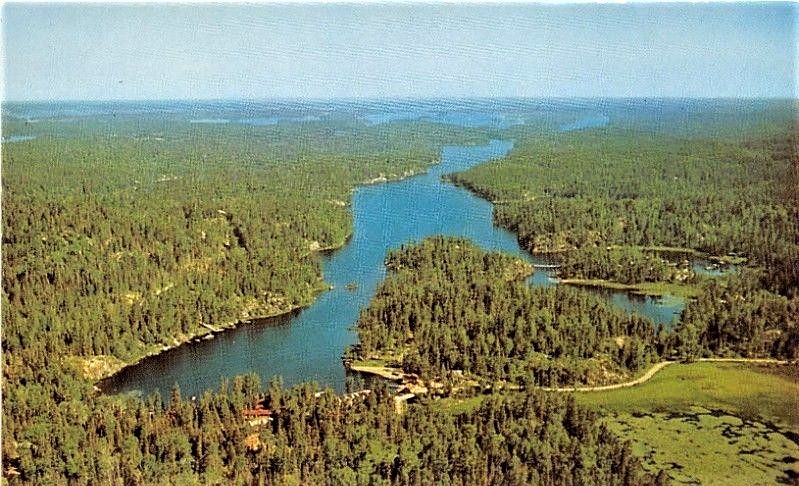

The old Gunflint Trail was also used as a supply route to mines that never produced anything and served as a logging road in the early 1900’s. As we traveled along this road, it felt as if we were going back in time because the paved surface, which lasted for 35 miles, transformed into a gravel road, then to dirt and finally to a two-lane cow path, which fulfilled the meaning of the word ‘trail.’ The entire Gunflint Trail was eventually paved ten years later in 1979.

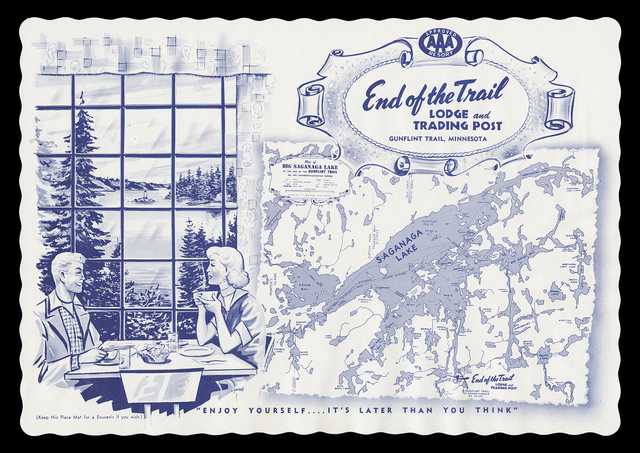

Various canoe outfitters lined both sides of the trail as we got closer to the end, and when I say “end“, I literally do mean “the end of the trail,” which stopped in the parking area of Saganaga Canoe Outfitters. In fact, the name of the building standing before us was the, End of The Trail Lodge and Trading Post.

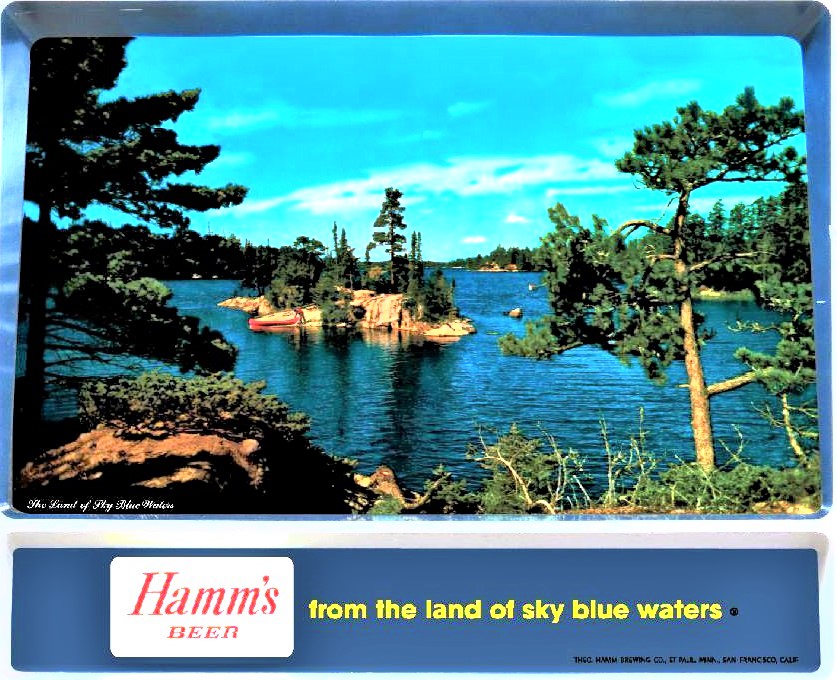

Although I did not realize it, I had been exposed to the BWCA while watching Chicago Cub baseball games on WGN-TV from the time I was born to the time of this trip (my Dad was a big Cub fan). The main sponsor advertising after each inning was the Theodore Hamm’s Brewing Co. of St. Paul, MN. They produced several TV commercials in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, which were filmed right here ‘in the land of sky blue waters’ at the end of the Gunflint Trail.

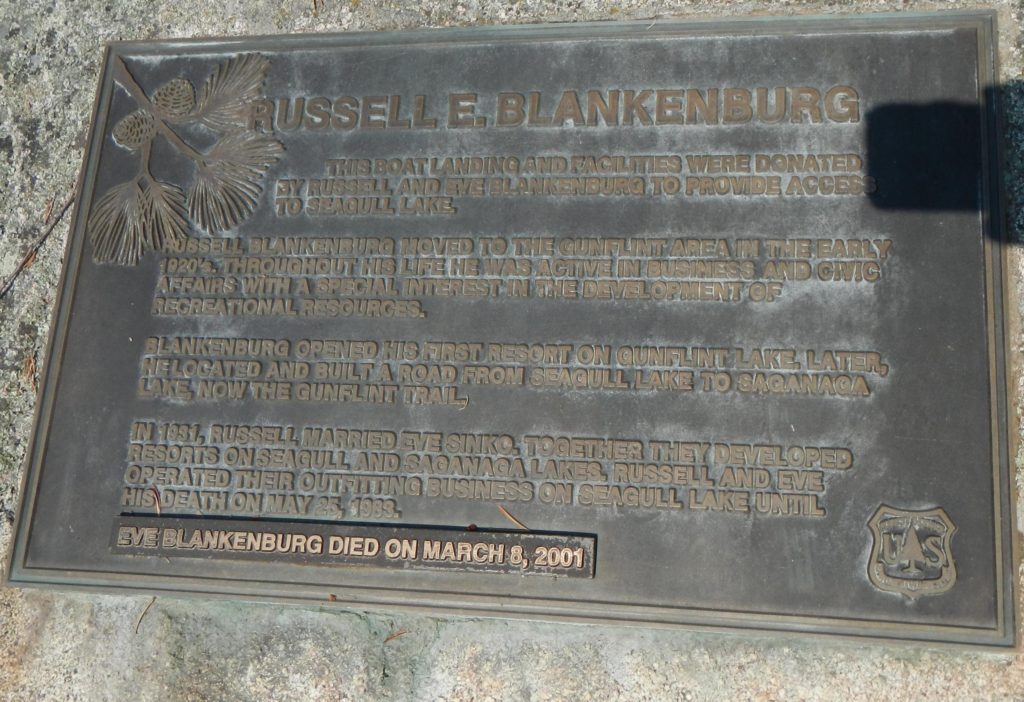

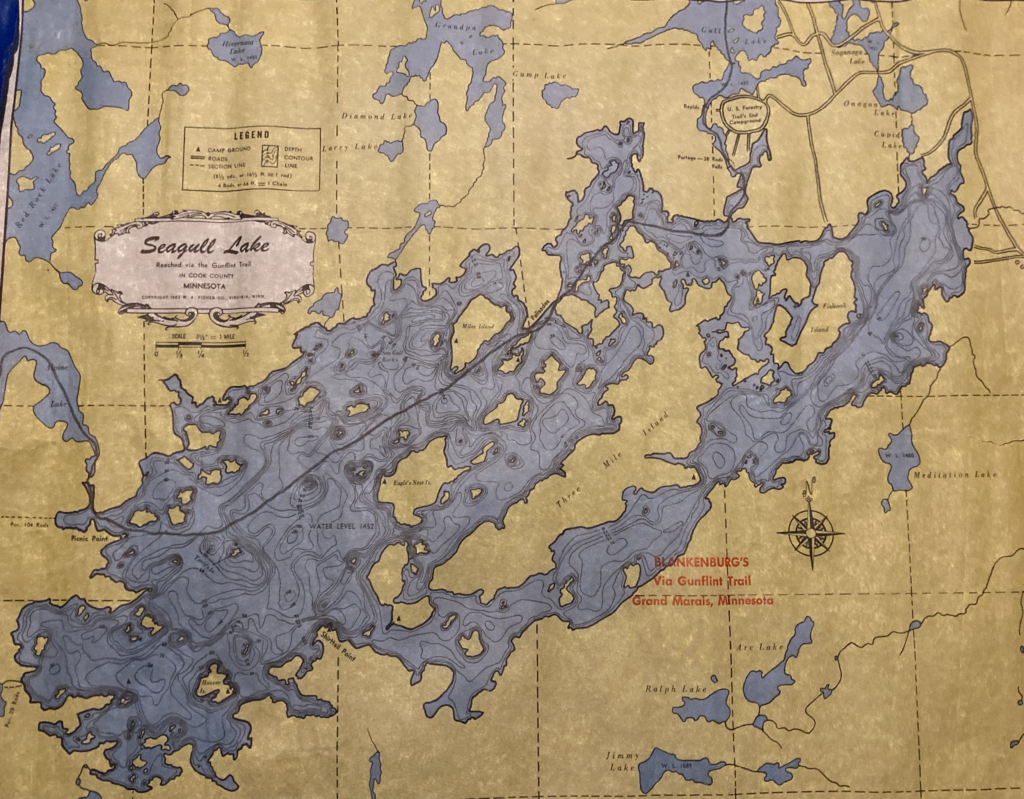

We were greeted by an elderly, grey-haired woman, who answered our knock on the door of a log-cabin style, rustic lodge. She was Eve Blankenburg, who with her husband, Russell, apparently single-handedly, took care of everything necessary to run the place. Russell, an elderly, grey-haired man, was off somewhere in a jeep, but soon came inside to aid us in our venture. The inside was what you always imagined a lodge in the forest would look like. Sofas, chairs, a large, stone fireplace; all very plain and practical, but very homey and pleasant at the same time. It was disappointing that we did not have time to enjoy it – we never even sat down. They showed us maps of the area, after we related our intentions, and together the four of us planned out our excursion. The maps were quite unique. While having the look and feel of 18th century parchment, very fragile and brittle, they were indeed just what the doctor ordered; durable and waterproof, which I was sure we would put to the test. We chose three maps and decided to plot our course in a circle. Our circle path would make it possible for us to get back to the Blankenburg’s in one day, if necessary, from anywhere we might be located. (No cell phones back then, but probably no service anyway.)

Mr. Blankenburg prepared our aluminum canoe with oars and life jackets. The rental for these items came to only $3.95 per day – Wowie! (It is $48.00 per day today.) I also rented an air mattress because mine had sprung a leak the night before. We unloaded the car and loaded up the canoe and Mr. B. gave us a shove off saying, “Good luck. See you back here in four days.” Although we did not know it at the time, I have since found out that the Blankenburgs were one of the first pioneers of the Gunflint Trail area. Russell was from Danville, Illinois and served in World War I. When he returned home after the war, he, being a talented baseball player, ended up at training camp for the Brooklyn Dodgers. But baseball did not really appeal to him, so he went back home. He heard about the Boundary Waters area and he and his mother began buying property along the Gunflint Trail, building the first lodge in 1926. He continued to buy up land and develop the area in a rustic manner for the enjoyment of nature.

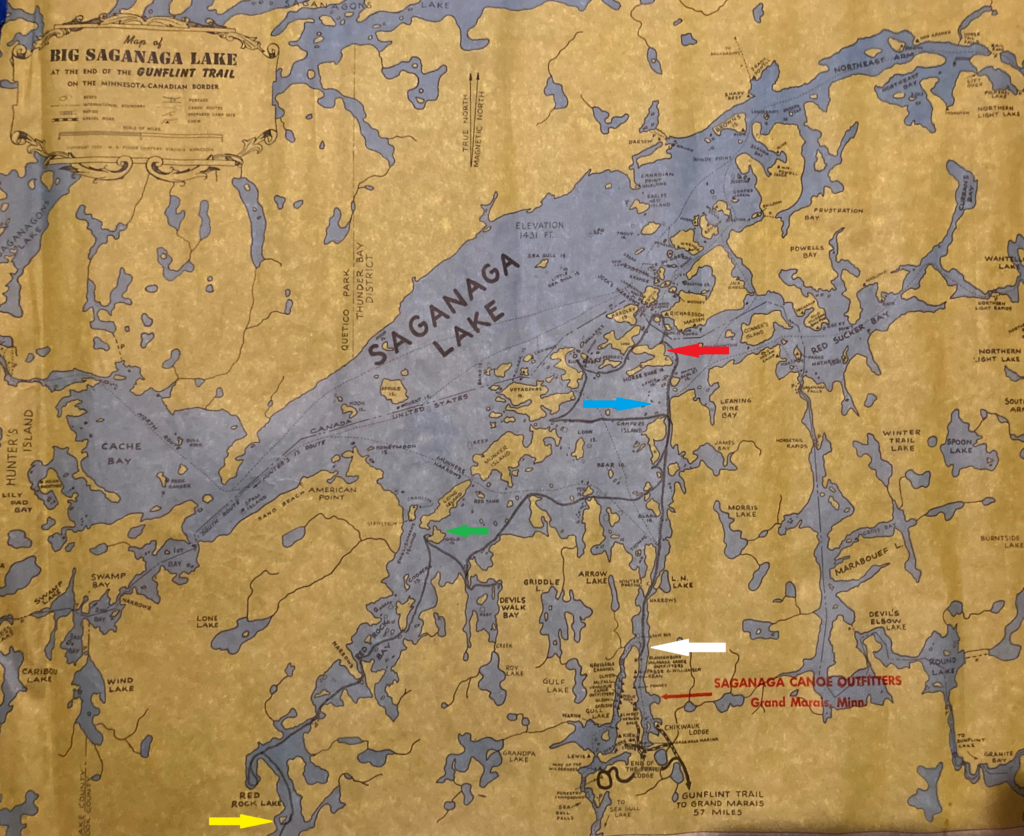

The white arrow on the map below indicates our starting place. We, of course, spent most of the day paddling, but it is important to get the knack of paddling as a team and not to paddle against each other. So, we practiced on our way and since canoeing was new to both of us, we decided to not go very far. We also, would be a bit green at setting up camp and wanted to be settled before it got dark. One of the maps had red dots indicating campsites, which had grill-type fireplaces and an outhouse without the house – it was just out! A wooden box to sit on in the woods – yikes! Keeping in mind the Blankenburg’s suggestion to camp on islands (there are no bears on islands), we chose Horseshoe Island (red arrow on map below), which was just on the U.S. side of the border and pulled our canoe up onto dry land. Across the water, we could see a Canadian flag flying over the Canadian Customs building. We had a little trouble setting up camp and having supper, which was always beef stew or beans. We slept well that night after a long, busy day.

The next morning, we breakfasted and packed up the canoe. We had only one canteen, which contained our complete drinking water supply (hmm, what were we thinking?) and we used most of it for supper and breakfast. Upon seeing a trading post on the Canadian side, we thought it a good idea to purchase some cans of pop. It took a while for someone to answer the door after we knocked; not a high traffic area, I guess. Mike had brought a metal cage for keeping fish, so we put the cans in it, tied it to the canoe and through it overboard to keep the cans cool in the lake. It may have created some drag, but the pop didn’t last very long anyway.

As we paddled along, we experienced what I call “the trickery of the two-dimensional land.” On the map, it is quite clear which is an island, peninsula or mainland because the map is a birds-eye view looking down. But down on the earth, looking across the water, it is very difficult to distinguish which is which until you are fairly close and by then you might realize you have gone the wrong way. You can see on the map some zigzagging took place and a couple of times we went into a bay by mistake and had to backtrack. It became quite windy out on the big lake, so we came up with a clever sail idea so we would not have to paddle. With my jacket on my lap, I put my arms into the sleeves and lifted my arms above my head and my jacket filled with wind and away we went! Great idea and we really zoomed along. You can see our ‘sail boat route‘ indicated on the map by the blue arrow – but wait! We thought we were headed south not east – whoops – unfortunate detour – better stick to paddling.

Suddenly, I noticed a very strange sound that was difficult to identify at first, but then it hit me – quietness – the peaceful sounds of nature! In keeping with the preservation of the wilderness experience, no boat motors were allowed in the water and there was a no low-fly-zone in the air above. It reminded me of Mackinac Island, where horses and bikes are used instead of cars. We made our way to Gold Island (green arrow), by far the nicest spot of all. It was quite a climb up to a flat-top clearing. It was surrounded by tall pines and gave the appearance of our being in a house with the sky as our roof.

Having run out of water and pop, we got water out the middle of the lake, which is supposed to be the cleanest. Just to make sure it was safe to drink, we decided to boil it in a pan. So, I held the canteen while Mike poured the boiling water into it. I know this sounds really dumb now, but I assure you, it seemed like a good idea at the time. Too bad we didn’t have a funnel. Needless to say, he missed the little hole and thoroughly doused my hand with the boiling water – ouch! I sprayed my hand with burn/bug bite, medical-wonder spray and wrapped it with a handkerchief. It really felt good, but did not last very long, so I kept spraying every so often. Our only injury on the trip. No more boiling after this episode, we just looked the other way and filled the canteen from the lake. We spent quite a bit of time lying there looking at the stars that night and saw several shooting stars – reminded me of being down at the dock at Camp Zion at night – total darkness.

After breakfast of day three, we went to the other side of the island, where there was a quartz deposit. It seemed to me that Mike knew this was there, but I don’t know how. Anyway, armed with our trusty, folding shovel/pick, we joined a couple of other prospectors who were attempting to strike it rich. We found some quartz crystals and brought them home as souvenirs of Gold Island. Besides these two, we only saw one other person on our adventure. We continued on our journey, now paddling like an Olympic rowing team, but still going into dead end bays now and then.

On this day, we encountered our first rapids/portage option. If the water is too low to navigate the rapids, then you can do the portage instead. Portage means to pick up your canoe and all your gear and carry them down a path around the rapids. A portage is measured in rods, in which one rod equals 16 1/2 feet. The rod is a surveyor’s measure, used because it can measure an acre in whole numbers. (Oh really? hmmm). The rapids didn’t look too bad, so we tied everything down and went for it – No problem. We went through rapids one more time and had to get out and pull the canoe through part of it. But the next time, we opted to do the portage of 48 rods.

As we pulled our canoe out of the water and onto the shore and began unloading it, a fellow came hobbling down the path toward us. He was an older man with a beard, who reminded me of actor Walter Huston in the movie, “The Treasure of The Sierra Madre.” He was carrying his canoe and doing the best he could with only one real leg and a homemade wooden crutch. He sat down by us and we talked for a long, long time.

“Howard” told us he had put in at Eli, MN, many miles to the west and had been out for a couple of months. That explained why he was sort of grubby and rough looking. He lost his leg serving in World War II and worked as a cherry picker in the summer. He had a false leg back home, but found a crutch would serve him better out in the wilds. It was a couple of strips of wood with a wooden block at the base. He related about the time he dropped his paddle in the lake and it floated away. He was able to use his crutch to paddle his canoe to retrieve it. We had loaded up with cans of stew and beans, but he had sacks of flour, soda, salt, sugar and coffee. He traveled the smart way by making biscuits from scratch and catching fish. We sent “Howard” on his way and faced the task at hand – portage. We used up a lot of time with him and then carrying our canoe and all our stuff down the path and back into the water again. Our hope was to get farther along on that day, but darkness was creeping in, so we found an unnamed island to camp on for the night. Unfortunately, we found a large rock with a chalk inscription on it when we came ashore. It read, “DANGER! BEAR ON ISLAND! RIPPED TENT!” We were told to camp on islands because bears are not on islands. So, was this message true or was it a joke? Best to think it to be true and prepare to be attacked in the night, because it was too late to travel anywhere else. Maybe it was the Hamm’s Bear. “Bear Island” is shown by the yellow arrow on the map above.

After setting up our tent, I built a log fence around it and spread dry leaves around the fence, so we could hear him coming. We slept with our machetes that night, but I was not prepared to kill a bear. Every time we heard a sound, we thought he was coming, but then it would be quiet again. When we finally drifted off to sleep, the great bear attack came! A loud strike against the side of the tent, made me leap into the air! But then, all was quiet and nothing moved. We came out of the tent in the morning to find one of the tent stakes had popped out of the ground and hit the side of the tent – no bear.

Our last day, we wound our way through some small lakes and made our way to the second largest lake in the BWCA, Seagull Lake. Since we were a bit behind schedule, we shot across in a pretty straight line. Near the end of our journey, in the narrow area, was a waterfall that we had to portage around. It was 38 rods this time, not too bad. As we returned to our starting point and paddled toward the End Of The Trail Lodge, we saw Mr. Blankenburg sitting on his dock talking to our new friend, “Howard.” They were looking at a map and sharing stories. I wish we could have stayed longer and listened to them, but we had to leave and so we loaded the car and headed for home.

Mike has continued to go out canoeing and so has all of his six children at one time or another. His son, Matt, has made regular trips to BWCA with a father-son group, thus involving a third generation in getting their feet wet. I bought a kayak and have explored many of Tennessee’s rivers and creeks. My son, Jacob and his wife, Mary, also have kayaks and we kayaked together in Nebraska this summer. And so, the adventures that began over 50 years ago continue on in our families today. But Hey! I gotta go – I just loaded up my kayak and I’m headed to the Stones River – no islands and no bears!