Take A Drive Through History

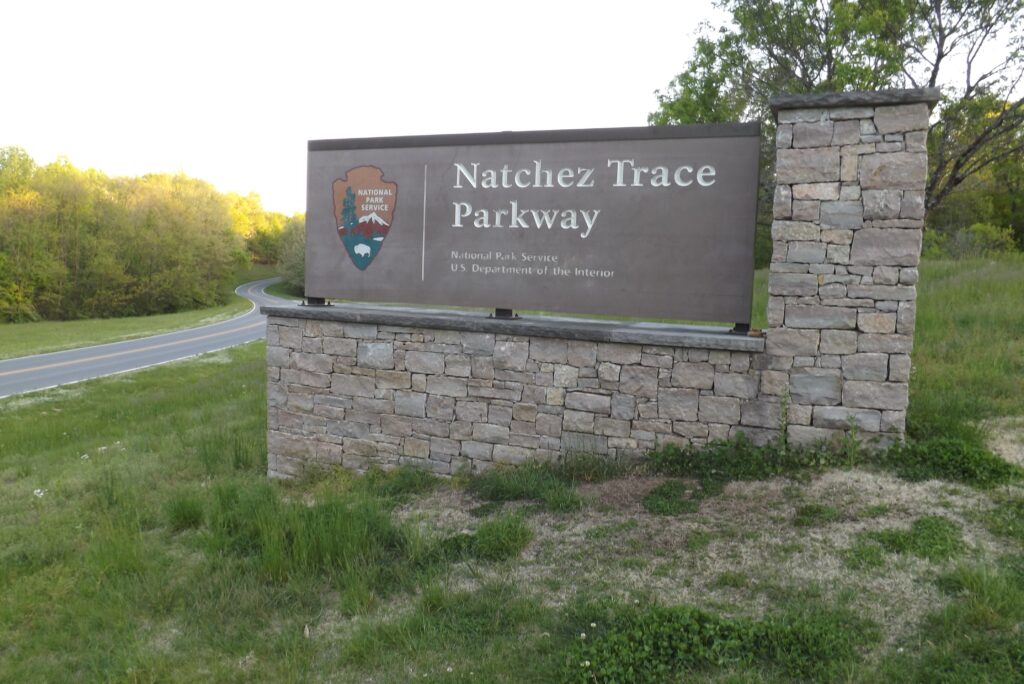

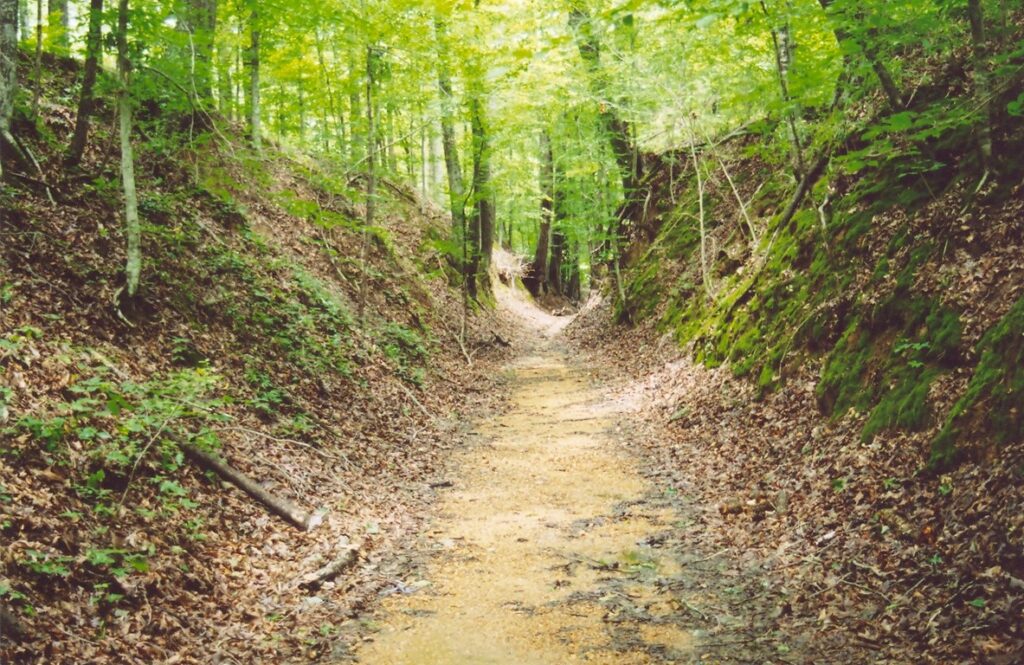

This is a photo of a section of The Natchez Trace, which is a 444 mile road from Nashville, Tennessee to Natchez, Mississippi. Let’s see how observant you are. What is wrong with this picture, is the absence of telephone poles, billboards, signs, fences and houses, because none of those items are allowed along the Trace. Also banned are, gas stations, restaurants, and stores. You will see an occasional wooden sign denoting an upcoming historical area where you can stop and also, wooden mile markers. Every so often you may see a old stone wall enclosure or a split-rail fence. And there are very few exits, so fill up your tank, bring your lunch and travel back in history on The Natchez Trace!

I would be amiss if I failed to interject some info about the Longhunters, who were pre-tracers, so to speak. Longhunters were pioneer hunters and explorers who made expeditions into the frontier territories of Tennessee and Kentucky in the 1760’s and 1770’s. They left their homes and families in the Colonies for periods of up to six months long, to hunt, trap and fish, thus the name Longhunter. Along their way, they noted the particular traits of the country as to waterways, mountains, wildlife and Indian tribes. They passed through the Cumberland Gap, which was found in 1750 by explorer, Thomas Walker. The Gap was an important pass through the Cumberland Mountains and the first “Gateway to the West” (sorry St. Louis), located approximately where the future states of Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia meet. Walker named the Cumberland Gap, Cumberland River and Cumberland Mountains in honor of the English Prince William, the Duke of Cumberland (best remembered for putting down the Jacobite Rising at the Scottish Battle of Culloden in 1746.) A four-lane tunnel was cut through the mountain in 1996 because the steepness of the Gap Highway caused many accidents.

Once through the Gap, the Longhunters followed the Wilderness Trail, (which was blazed by the most famous Longhunter, Daniel Boone) and the animal/Indian trails. Other important Longhunters were; Kasper Mansker (Mansker’s Station), Uriah Stone (Stones River) and Isaac and Antony Bledsoe (Bledsoe’s Creek, Bledsoe’s Lick and Bledsoe County.) 200 years later in 1974, Tennessee’s Long Hunter State Park was created along the Stones River in their honor.

Meanwhile, back to the Trace . . .

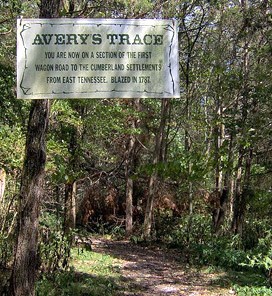

What in the the world is a Trace anyway? Well, the word trace, as a noun, means “a surviving mark of a former existence.” The main highway that goes through Hartsville, TN is The Avery Trace, which is more recognizable as State Route 25. This Trace has no restrictions of any kind and appears as any other ordinary road, except for an occasional sign of designation. I and many others, travel this road every day, but most of them do not realize they are following an old buffalo trail. More correctly called a bison, these large animals are usually thought of as creatures of the American Wild West days of Cowboys and Indians. The truth is, the bison herds roamed all over the United States.

Ok – time out! – bison or buffalo? Here’s the truth, if you can handle it! There are not now nor has there ever been buffalo in North America. Wait, what? But what about Buffalo Bill? Sorry, it should have been Bison Bill; and Bison chips, and “Oh give me a home where the buffalo bison roam.” Buffalo, although very similar to bison, are only found in Africa and South Asia. So take a minute to cry or whatever and let’s get on with the show.

The bison traveled the easiest route they could find that led them to water and salt. Tennessee is loaded with rivers, streams and creeks, so that was an easy find for them, but salt licks, as they were called, were much more scarce. But there was a salt lick a few miles from Hartsville and that is where they were headed. The Indians were smart enough to follow the animals and their trails and the white settlers who came later, did the same. It is easy to see how these trails eventually became known as a trace.

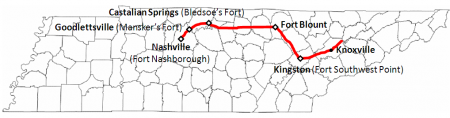

In 1787, the colony of North Carolina ordered a road to be cut to lead settlers to the new Tennessee Territory. Many Revolutionary War soldiers received land in the TN Territory as compensation for their service and were anxious to stake their claim and settle down. Peter Avery, a local hunter who was very familiar with the area, was chosen for the task of laying out the path. Of course, he used the ‘trace’ that had already been established by the bison and the Indians and widen and smoothed it out into what became known as Avery’s Trace. The Trace soon became the principal route as it wound its way from east to west through Tennessee connecting five forts; Fort Southwest Point, Fort Blount, Bledsoe’s Fort (site of the salt lick discovered by Isaac Bledsoe), Mansker’s Fort (site of another salt lick discovered by Kasper Mansker) and finally, Fort Nashborough (Nashville) on the Cumberland River. The forts provided shelter and protection for the travelers. By the way, Isaac Bledsoe wrote that the bison were so numerous that he did not want to get off his horse for fear of being trampled by the beasts. Hard to imagine how wild it was here back then.

But hey, I thought we were talking about The Natchez Trace!?!

For us Tennesseans, the Natchez Trace begins just south of Nashville off Highway 100. The real beginning is, of course in Natchez, Mississippi. Named for the Natchez Indian tribe, whose descendants mostly live in Oklahoma today, the original tribal home was in the area around the city of Natchez. There is a State Historic Site southeast of Natchez. As you travel the Trace, you can stop and visit historical sites that are marked along the way. There are also, detailed maps that point out important information, as well as signs and markers. A few hiking trails follow the old original Trace through the woods.

The early settlers mainly living in the Ohio River Valley (the areas north and south of the Ohio River, which flows into the Mighty Mississippi) would float their crops, livestock and other materials down the rivers on wooden flatboats to the major cities of the Mississippi River; Natchez, MS, founded by the French in 1716 and New Orleans, LA, founded by the French in 1718. They would not only sell their goods, but also their boats for lumber because travel against the upriver current was not possible. (The steamboat was not developed for use on the rivers until the 1820’s.) The second half of their trip was the long walk or horse ride back home on – you guessed it – The Natchez Trace! In 1801, President Thomas Jefferson had designated the Trace as a National Post Road and by 1809 it was improved enough for wagon use.

As traffic increased, some settlers built houses along the Trace and opened “stands” (another word for inns.) The stands were most often named after the family who owned it; Mitchell’s Stand, McIntosh’s Stand, McLish’s Stand, Hawkin’s Stand, Pigeon Roost Stand, and so on; 36 in all. Each stand was a bit different, but basically had food and some degree of lodging, but very few beds. Travelers sometimes would sleep on the floor, the porch or outside. Some had taverns and a few had ferries to cross rivers and streams. My favorite one is Sheboss Stand. A widow operated this stand with her second husband, who was a Chickasaw Indian. He spoke very little English and when a traveler asked him about accommodations, he would point to his wife and say, “She boss.” I stopped at Gordon’s Stand, which is one of the very few still in existence. The Gordons also operated a ferry across the Duck River.

There were countless others who traveled the Natchez Trace; peddlers, trappers, highwaymen (robbers who stole from travelers) and circuit preachers, who were part of the Second Great Awakening, which took place about 1790 to 1840.

Meriwether Lewis and Grinder’s Stand

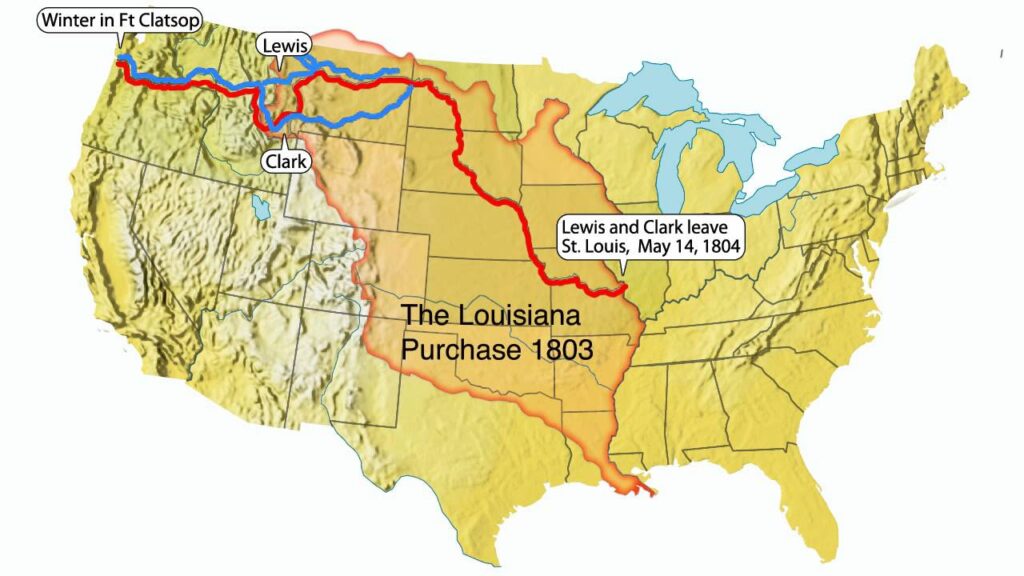

The most well known of the 36 stands along the Trace was Grinder’s Stand, near Holenwald, TN. It was here that famous American Explorer, Meriwether Lewis died under mysterious circumstances in 1809. If you recall what you learned in school about the Louisiana Purchase, you know that the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803, nearly doubling the size of the U.S. at that time. Almost immediately, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned his friend, Meriwether Lewis to organize an expedition to explore and map out this new wilderness. Lewis chose William Clark to accompany him as co-leader of the famed, Lewis and Clark Expedition when they and their group of 30 men left St. Louis, Missouri (the second “Gateway To The West”) in 1804.

The group returned to St. Louis in 1806, and Meriwether Lewis was appointed by President Jefferson as Governor of the Louisiana Territory in 1807. He took up residence in St. Louis and in September of 1809, he began a trip to Washington D.C. As he traveled along the Natchez Trace, he stopped at Grinder’s Stand for the night. It was here that his life ended, sometime in the dark of night. There were a few different versions of what really happened that night. The most popular at the time, was suicide. As was mentioned earlier, highwaymen frequently robbed and sometimes killed travelers, so this was also a possibility. In 2022, a movie was made, “Mysterious Circumstances: The Death of Meriwether Lewis.” It is quite unique, in that it relates the various scenarios which could have caused his death by retelling the story over and over with each variation. In 1848, Lewis’ body was exhumed from his grave next to Grinder’s Stand, so it could be examined by a medical doctor as to the cause of death. The conclusion was that he died by the hand of someone other that himself. It was not possible at that time in history to reopen the case and track down the real killer without the modern forensic techniques of today. So, that was the end of the story and the mystery continues. After the body was reburied, a monument was erected at his grave site. It is ironic that Meriwether Lewis survived the dangers of his two year expedition with William Clark; covering 8,000 miles of uncharted territory, crossing rivers, encounters with various hostile Indian tribes, climbing dangerous mountains, becoming lost in a snowstorm, nearly freezing to death, etc. and then is shot to death in bed in Tennessee.

The monument style of a broken column, symbolizes ‘a life cut short.’ A replica of Grinder’s Stand was built near the ruins of the original building.

Another Stand of importance near Natchez, MS is the Mount Locust Stand. Built in 1780, it is one of the oldest buildings in Mississippi. It was both a traveler’s stand and a cotton plantation. Serving as a private residence until 1934, it now is open to the public for tours and exhibit viewing.

Although the Stands were plentiful along the Trace, there are many other points of interest as well. Moving up the Trace closer to Jackson, MS, we come to the site of The Dillon Plantation, which served as Union Headquarters for Generals Grant and Sherman in 1863 during the Civil War Battle of Vicksburg. North of Jackson is a Cypress swamp with a walking bridge just off the Trace. Further north, just below Tupelo, we find the winter camp of Spanish explorer, Hernando de Soto. De Soto stayed here in 1540 while he was leading the first European expedition to cross the Mississippi River. He also traveled through Florida, Georgia, Alabama and Arkansas. He died two years later of some unknown fever on the western bank of the Mississippi River. The site of a Chickasaw Indian Village and several Indian burial mounds are in the northern section of Mississippi before the Trace enters the 33 miles across the corner of Alabama.

The Tennessee Volunteers

I previously mentioned several interesting places on the Trace in Tennessee, but there are two more special features to highlight before we end our journey. The first one has to do with the War of 1812. Addressing a group of Tennessee volunteers, which included Private Davy Crockett and Lieutenant Sam Houston, Major General Andrew Jackson declared, “Brave Tennesseans! We must hasten to the frontier, or we will find it drenched in the blood of our fellow-citizens!” TN Governor, William Blount had called for 3,500 volunteers, but 5,000 came forward to form Jackson’s group. They marched south on the Natchez Trace and ended up defending New Orleans and beating the British Army in 1815.

- Answering the call for help from the small group who were preparing to defend The Alamo near San Antonio, Texas, Tennessee’s Davy Crockett arrived with a band of 30 volunteers in 1836.

- U.S. President James K. Polk, himself a TN native, requested 2,800 volunteer soldiers from TN to go fight in the Mexican-American War of 1846. To his surprise, 30,000 TN volunteers answered his call.

- The Volunteer spirit continues in Tennessee up to the present day. In March of 2024, TN Governor Bill Lee asked for 100 National Guard volunteers to go to the Texas border again; this time to help stop a different type of invasion and 400 volunteered to go.

We shall end our trip on The Natchez Trace at the beginning of the Trace in Tennessee (which is really the end, as the true beginning is in Natchez, MS.) In 1994, the Double Arch Bridge over Birdsong Hollow was completed. The design and construction of the bridge has won many awards. It is, in fact, one of only two post-tensioned, segmental concrete-arch bridges in the world. It is quite breath-taking in person, at 155 feet high and 1,572 feet long. As you begin your journey back in time, you must cross this mighty structure, which contrasts the amazing strides in transportation of modern engineering with our humble beginnings on a footpath. I enjoyed my travels on The Natchez Trace and I am sure that you will, too.